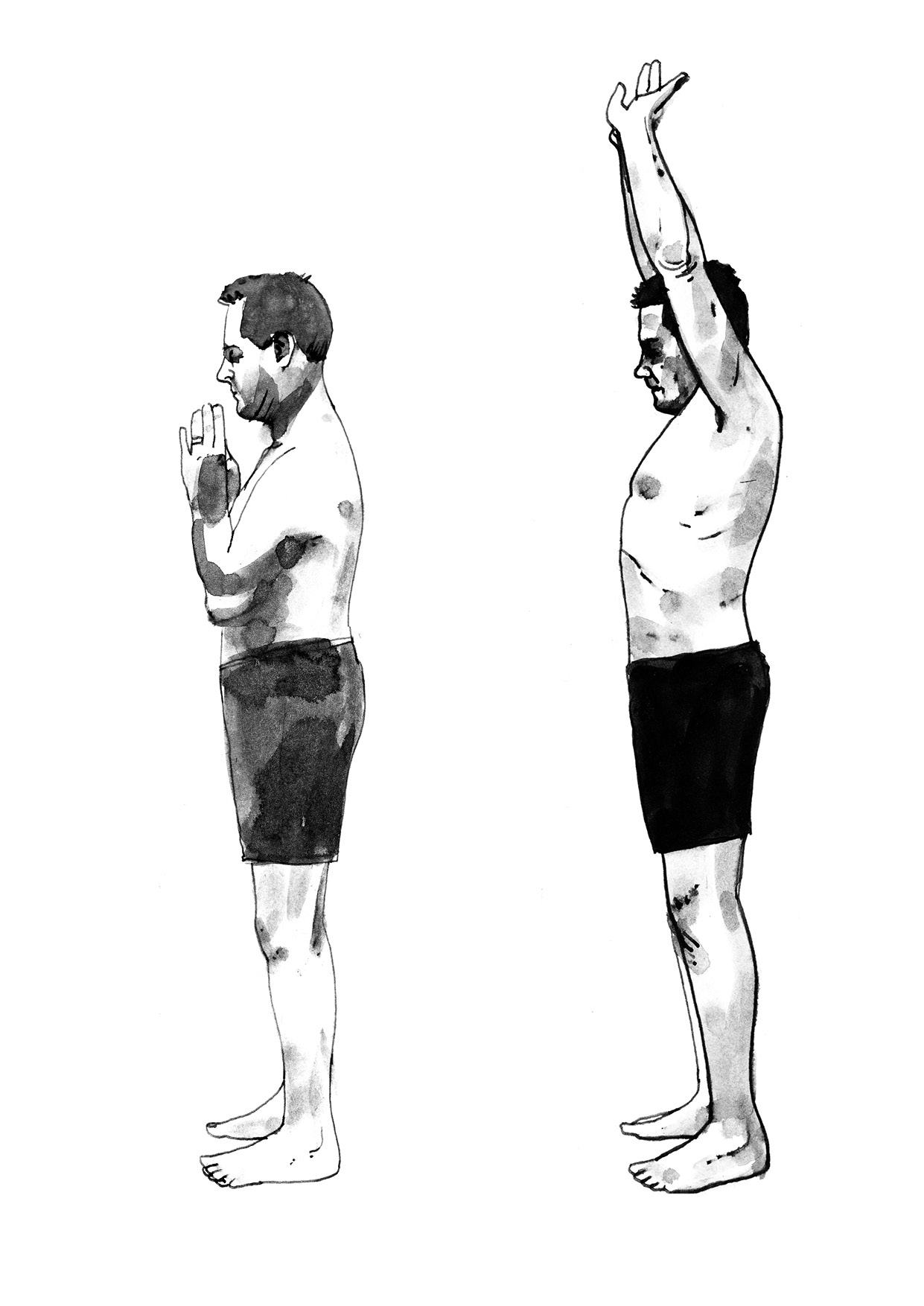

Uttanasana

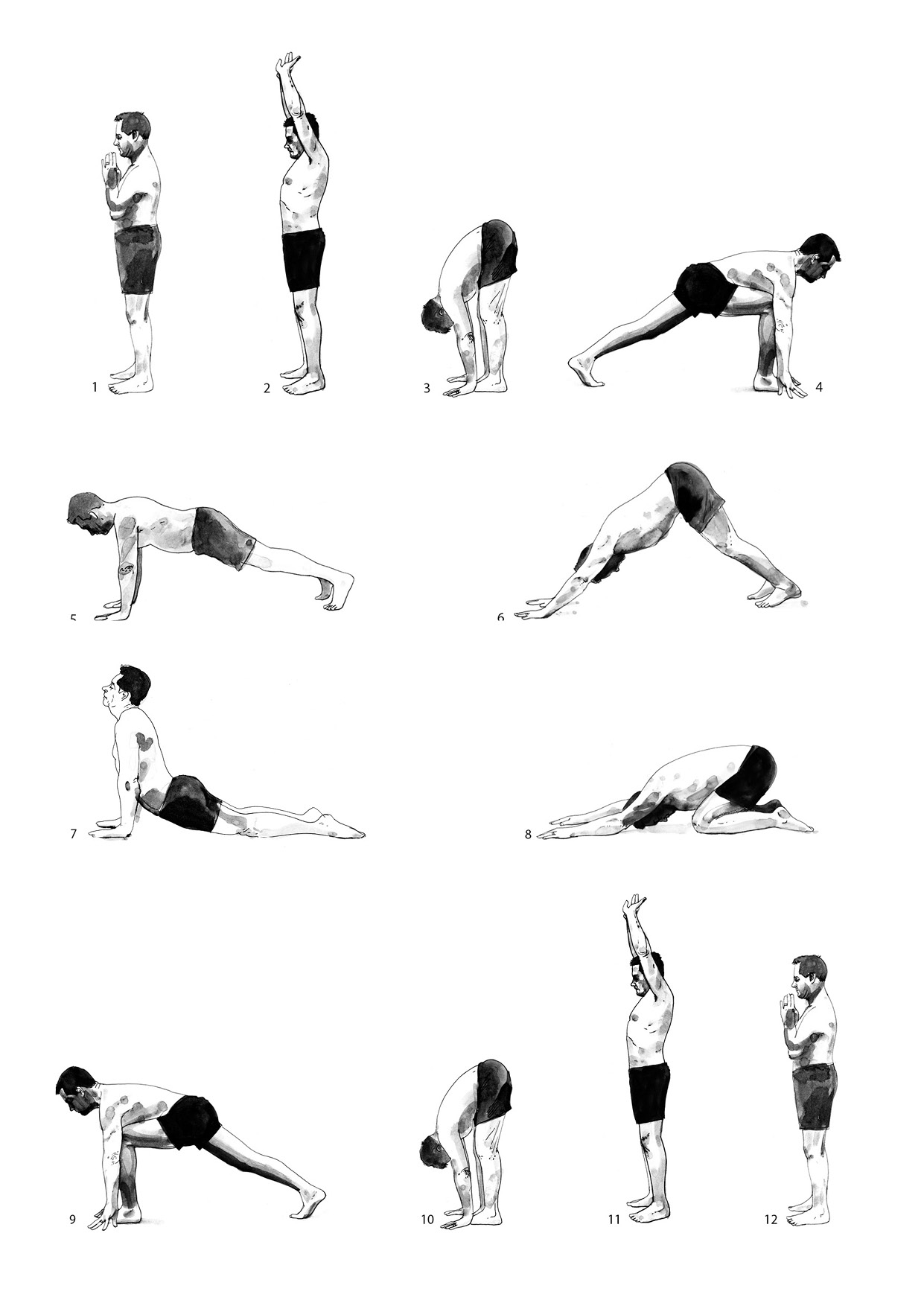

The Salute to the Sun, like most things in Yoga, has many variations. The one we use here consists of seven ‘asanas’, to use the Sanskrit name for positions, done in a 12-step sequence. This posture is one of the Iyengar yoga system’s basic components, used as a relaxation between more strenuous positions, although until the backs of your legs lengthen nicely it’s hard to see how it can be relaxing!

‘Ut’ indicates deliberation or intensity and ‘tān’ means to stretch, extend, lengthen. The head-down position slows the heart and soothes the mind, giving an extreme stretch to the spinal column, which rejuvenates the nervous system and gets the Pran (or Ch’I, or life force) really flowing.

It’s also, if you’re not already very limber, excruciating on the backs of the legs, which have to be kept ramrod straight with the knees locked, the kneecaps pulled up at all four corners. So there are intermediate positions on the way where you can use blocks to rest your hands, or even lean against a wall and stretch your arms out to a chair or suitable platform at the right height.

As in all asanas, the trick is keeping one (or some) parts of you energised and tight, which allows other parts of you to relax and let go as much as possible – which is how you get the stretch. Only by creating a strong and solid framework or foundation from which to ‘hang’ the parts that you want to go loose will you be able to let them go and get the full benefit of the stretch.

This is the second posture in the sequence, so you are coming to it from Tadasana, the standing mountain. Your arms are stretched to the full vertically above your head, the fingers linked and ideally the palms flat and facing outwards and upwards. Your coccyx is tucked in, the bottom of your pelvis tipped forward a little to flatten out the ‘lordosis’, the inward curve of the spine above your buttocks. On the outbreath, bring your arms, still straight, down to parallel with the floor at your eye level, then use them to continue downwards and stretch outwards as you bend at the hips. Take another breath if you need to, and go down on the outbreath. It’s crucial to keep the top half of your body open as you bend. Don’t curl up your spine and crunch up the front of your body, but keep your head up and your back straight, bend from the hips and, still keeping your head up and your back in an upward curve, let your hands head for the floor. At their nearest point – ideally on the floor, but this won’t happen if you’re new to this position, unless you’re unusually limber – legs still locked solid and straight, kneecaps pulled up, you let your head and neck go and allow gravity to do the work of extending them towards the floor. Pay particular attention to the back of your neck, which is usually under extreme tension because it has to hold your heavy head up all day. Just let it go, feel it lengthen. Let go in the shoulders and between the shoulder blades.

If it’s hurting the backs of your legs, which is pretty much a given when you start, try to get that trick of relaxing into the stretch – letting go. A lot of the result comes from being able to ‘make space’ in the hips, which allows the top half of your body to lengthen and come closer to your thighs. Feel your vertebrae separating and your whole spine stretching. Don’t push. Never push, it won’t work. Let go in your hips, feel the stretch on the muscles in the backs of your legs, and selectively pull them up towards your hips, which act as a pivot from which your lengthening top half will continue to lower towards the floor.

If the backs of your legs are shrieking so much that you are tensing up, especially in the back and shoulders where it is most likely to happen, give yourself a break and do it in stages. Use blocks or bricks or anything that raises the level to which your hands will drop, or do the chair and leaning against the wall thing. The benefit of this pose rapidly becomes apparent. It automatically quietens your mind. On each outbreath you can feel the top half of your body getting a little longer. Blood goes to your head, which is good, but if you feel dizzy, come up – always leading with your head, your back as open and extended as you can make it.